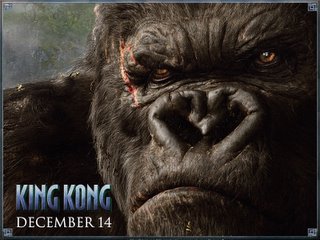

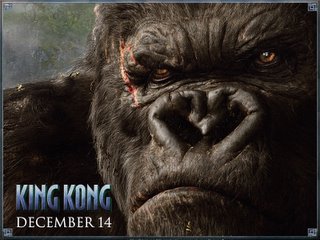

So we went to see King Kong on New Years Eve. E and I were especially excited to see it, especially after the excellent reviews it has been getting. I had read aloud the Movie Mom review on Yahoo (I trust her reviews quite a bit) and we felt like it would be a great way to spend a few hours on this rainy vacation. I’m a sucker for grandiose, imaginative portrayals of fantastic creatures as it is. A wonderfully indulgent way to celebrate New Years Eve.

But I was disappointed and even troubled by the experience. So troubled, in fact, that it has taken me a couple days to find some of the right words to put around it. And it’s really just words that I have—not even well-formulated sentences yet! So, as a way of beginning, here are some of the words floating in my mind in connection with King Kong (2005): colonialism and a postcolonial critique; sexism and a feminist critique; racism; “othering”; hierarchical portrayal of human-to-human, and human-to-animal relationships; fear of the unknown, the passionate, the ecstatic; militarism; imperialism and U.S. film industry.

I wasn’t expecting to be confronted with these themes when viewing King Kong! I was expecting pure entertainment fluff. But as I’ve thought about it more, I realize I should have known.

King Kong reached mythic status in North America long before this latest remake. It both shapes and is shaped by North American values and perspectives. In the little bit of reading I did before beginning to write this, I found that there have been tons of things already written about the phenomenon that is King Kong. It makes me hesitate to add anything to the mix, because I am aware of how much I do not know about what has already been said! But I embark nonetheless.

I was lucky to catch the last hour of the original King Kong on TV yesterday afternoon. The 1930’s version was tremendously un-self-reflective to the degree that it is almost innocent—in a way that Jackson’s version never could have the luxury of being. Not in the twenty-first century.

For example, Jackson’s portrayal of the relationship between Kong and Ann Darrow reflects a greater appreciation for Ann Darrow’s agency. This was never the case in the 1930’s version in which Ann continues to remain deeply frightened of the Ape-Monster. In contrast, Jackson’s scenes of Kong and Ann’s mutual appreciation for the beautiful are captivating. And Kong’s comprehension and later acquisition of Ann’s sign for “beautiful” is reminiscent of the famous gorilla Koko’s use of sign language. Not only does this reveal a deepening of Ann’s character, but a profound blurring of the line between human and beast that remained more distinct in the earlier version.

However, it was the shocking portrayal of the inhabitants of Skull Island that I found disturbing. Jackson chose to represent the indigenous people as Zombies, an idea that has been perpetuated in reviews of the film. The grotesque and unsympathetic creatures are depicted as being subhuman and soulless apparently so that we will not feel any remorse when the White men invade and ruthlessly slaughter them with machine guns. However, it’s clear that Jackson himself was conflicted about his interpretation by the brief essay included on the movie’s website. (Go to the home page, click on Special Features, and select “Skull Islanders” to read the essay. There is no way to link you directly to it.) In this essay, we learn that the Skull Island inhabitants are organized in a matriarchal society that has learned to survive through ecstatic ritual experiences culminating in the sacrifice of young women to the beast Kong. The matriarchal aspect was not evident to me upon first viewing, but in retrospect I could recognize that the shaman was indeed a woman and the leader of the people. By this we can only conclude that the skull island inhabitants are not subhuman, living-dead creatures, but indigenous human beings organized into social and religious systems.

One of the essays I found online (on the 1930's version) makes the excellent observation that the spectacle of King Kong turns its audience into monsters. He points out that Kong is splayed out in chains for the Broadway theater audience in the same bodily position as Ann Darrow was in when being sacrificed to Kong on the island. In this way, we see that the theater audience is as insatiable in its appetite for consuming the Other as entertainment as Kong was insatiable in his appetite for the young women being sacrificed to him. However, there is yet one more layer to this—which is that the audience in the movie theater is likewise insatiable. We are made into monsters, consuming the Other for our own entertainment. Somewhere in this is the connection between imperialism and the U.S. film industry. And it seems to be implied in the (again) insatiable desire of Karl Denham to capture the unknown, exotic world of Skull Island on film for mass consumption. No matter the cost.

Before seeing the film on Saturday, I never would have thought that I would be forced to face such issues after seeing Jackson’s Kong. In some sense this makes the film rather dangerous—because it is put out there as being mere entertainment, nothing more. But the mythic quality of King Kong for the U.S. makes it much more than entertainment. It is reinforcing dangerous (1930's?) social assumptions and doing so in a medium that suggests it does not require critical reflection.

For this reason, I highly recommend the movie. And I would suggest that you rent the 1930’s version first. For a couple reasons. First, because honestly a great deal of the “charm” of Peter Jackson’s version is how much he remained faithful to his source material, with the same loving reverence as he did with Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. But also because it will serve as a touch point for critical reflection, especially in relation to the inhabitants of Skull Island, the portrayal of the relationship between Ann and Kong, and the agency of Ann’s character.

And now, that’s all for me. Peace and Love.

No comments:

Post a Comment